Wild poppies – photo by Liz Mathews

The centenary of the Great War’s outbreak is being marked in many ways; two projects have particularly moved me.

The first is Neil Astley’s new Bloodaxe anthology of war poems: The Hundred Years’ War, which includes this poem by Valentine Ackland, which I suggested for the collection.

How did they bury them all, who died in the war?

From near and far the tidy packed masses were neatly

Disposed, laid straight, boxed and buried; in a soil

Crowded already and crammed with the old wars’

Great litter of lives spilt. And they buried them all

As the gardener after the autumn fall

Digs in the apples to rot. So the summer’s spoil

Wastes down to mud and the sweetness goes rotten.

They buried them all, and the trees have already forgotten.

(Valentine Ackland, published in Journey from Winter: Selected Poems of Valentine Ackland, edited by Frances Bingham, Carcanet, 2008.)

I’m very pleased Neil chose to include the poem, which is such a powerful statement about the waste and mortal cost of all wars. I read the poem at the pre-launch of the book at Lauderdale House in Highgate, and felt its power to move the audience as I did so.

The reading brought out the breadth of the Bloodaxe anthology, and its global scope; among the highlights Stephen Watts read Isaac Rosenberg’s Louse Hunting brilliantly; Andrew Motion read some of his recent ‘found poems’ taken from soldiers’ own accounts of war; David Constantine read a very moving poem about his grandmother Soldiering On; and Imtiaz Dharker read her superb poem A Century Later, about the Taliban attempt on schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai’s life, which concludes:

A murmur, a swarm. Behind her, one by one,

the schoolgirls are standing up

to take their places in the front line.

I also enjoyed hearing Dawood Azami read some of his poems in the original Pashto, as well as in translation, and it was a pleasure to hear Neil Astley read B.G.Bonallack’s The Retreat from Dunkirk, also in this wide-ranging anthology, which is one of the texts lettered on Liz Mathews’ monumental artist’s book Thames to Dunkirk.

This is an enormous collection; it contains six hundred pages of poetry, some familiar and necessary (Wilfred Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth, from the First World War, Antonio Machado’s The crime was in Granada, about the killing of Lorca during the Spanish Civil War, Martin Niemöller’s chilling First they came for the Jews… from the Second World War), also much that’s less well known. There’s a striking amount of work in translation, so that war is seen from many perspectives – not just by Germans in the opposite trenches, but also contemporary Taliban fighters. There are many different voices – witnesses, combatants, conscientious objectors, civilians caught up in war, refugees and prisoners, nurses and children.

Women are well-represented, considering the inevitable surplus of soldier-poems in the era the book covers; Anna Akhmatova writing during the seige of Leningrad, Denise Levertov hearing the guns of Dunkirk, Muriel Rukeyser in Spain, Nelly Sachs remembering the Holocaust – they’re all here. I found particularly moving the Polish poet Anna Swir’s poem He Was Lucky (which Neil Astley also read):

The old man

leaves his house, carries books.

A German soldier snatches his books

flings them in the mud.

The old man picks them up,

the soldier hits him in the face.

The old man falls,

the soldier kicks him and walks away.

The old man

lies in mud and blood.

Under him he feels

the books.

So, this is an important anthology, and a tragically contemporary one. Although there’s a reason other than shock value for every poem to be there, many of them are horrific and disturbing. To me, those that are most successful are those – like Valentine Ackland’s – that lament or protest or bear witness or speak defiance imaginatively, rather then by direct reportage. But this book rightly represents every kind of poetry-writing on war.

Neil Astley’s introduction notes ‘individual voices bearing witness to our shared humanity’, but also a disastrous inability to learn the lessons of history. “As Germany’s Günter Kunert writes in his poem On Certain Survivors, in which a man is dragged out from the debris of his shelled house: ‘He shook himself/ And said/ Never again.// At least, not right away.’”

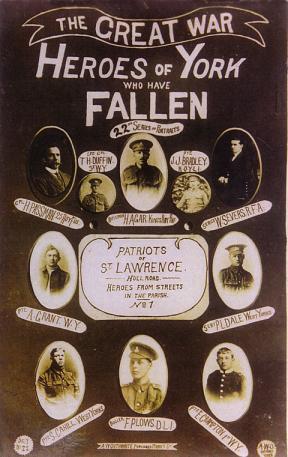

World War I postcard, with a photograph of my great-uncle T.H. Duffin among the portraits of Heroes of York.

I’ve also been involved in the Imperial War Museum’s centenary project Lives of the First World War, which is to be a permanent digital memorial, recording the experiences of millions of people during the war. Like the museum itself, the object is not to glorify war, but to acknowledge the contribution of the many people who were involved in the conflict.

I’ve been adding details to the life-story of one Thomas Howard Duffin, my grandmother’s older brother, who died in the Dardanelles campaign. Since he was killed when he was only 18, when my grandmother was still a little girl, half a century before I was born, I’ve never really thought of him as a great-uncle, only as her favourite brother Tom.

Tom Duffin’s photograph from The King’s Book, York Minster (Reproduced by kind permission of the Chapter of York)

Because he was a casualty of war, it’s easier to find out what happened to Tom than to trace the war experiences of his older brother Reggie, who survived. Poor Tom joined up as soon as volunteers were asked for, in August 1914, when he must have been under age, and trained with a battalion (9th, West Yorkshire Regiment) of Kitchener’s New Army. He and his comrades inhabit their historical moment, eagerly enrolling to defend (as the official message of sympathy had it) ‘the noblest of causes’, with all the naive arrogance and enthusiasm of youth, only to find themselves fighting an unknown enemy on foreign ground, for a theoretical tactical advantage which even at the time was considered by many to be a mirage.

This was Gallipoli, the Turkish peninsula not so far from Troy, which the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force attempted to capture. There, they faced extreme problems of missing equipment, bad supplies, no water, inefficient reconnaisance, chaotic planning and a bizarre over-optimism. Muddling through was one of the Empire’s specialities, however, and these new soldiers fought ‘with great pluck and grit’. Tom’s battalion received a special mention in the commander’s despatch on the landing at Suvla Bay, which remarks that they ‘deserve great credit for the way [the assault] was delivered in the inky darkness of the night’. (Sir Ian Hamilton’s Third Gallipoli Despatch)

After going through three months of intense trench warfare in extreme weather conditions, under almost constant bombardment, Tom fell ill of dysentery – which killed more troops than the actual fighting. Ambulance trains took some of the sick and wounded to hospital in Cairo, and it seems Tom was one of these lucky ones. (Many others died on the hospital ships, and were buried at sea, or died on the battlefield without ever reaching hospital.)

Sister Margaret B. Weatherup, of the Giza Red Cross Hospital in Cairo, wrote home: ‘I don’t know how many cases are in now – wards, balconies and corridors are full. The Dardanelles fighting has been very much worse than in France, at least the men say so. When one batch of stretcher cases came in we were not expecting them. A great many of the elite of Cairo, who were dining at their clubs when the news spread that an ambulance train with very serious cases had arrived, just came out to the hospital as they were, and carried the stretchers in. It looked strange to see four men in evening dress carrying the stretchers. Lord Edward Cecil was one of the helpers. It is not long since he lost his only son.’ (British Journal of Nursing, September 18, 1915.)

A VAD ambulance driver, Alice Christabel Remington, in an IWM interview, recalled: ‘The men that had dysentery, poor things, that was really terrible because they couldn’t be looked after and they were in a shocking state. I used to feel so sorry – they were so ashamed of themselves, they couldn’t help it, but sometimes the smell was simply frightful… The ones that had trench fever and the ones that had dysentery were the most depressed.’ (quoted in The Imperial War Museum Book of the First World War, Malcolm Brown.)

Tom died on 29th November, 1915, and is buried in the Cairo war memorial cemetery. Numbered among the disastrous casualties of the Dardanelles campaign – abandoned a few weeks after Tom died, when the army evacuated the peninsula – these horrible trench-illness deaths seem singularly futile. Like ‘friendly fire’ losses (then called ‘misdirected fire’) it’s hard to envisage such accidental deaths as ‘sacrifices for… Freedom and Justice’, or to make them seem heroic. It seems so wasteful and pointless for Tom to have not had a life, when his death didn’t serve any possible purpose.

Although I’d always vaguely known that he died at Gallipoli, now that I know what happened to Tom in a little more detail I feel – belatedly – as well as a distant sadness, the anger.