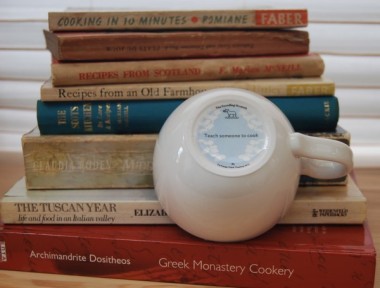

Exchange cup – photograph by Liz Mathews

‘There is altogether too much fuss made nowadays about the Art of Cooking,’ the Mad King of Chichiboo used to say. ‘Everything is good to eat so long as it’s hot enough and has grated cheese on top.’ (John Verney, The Mad King of Chichiboo, 1963)

In exchange for a china teacup (number 85 of Clare Twomey’s installation Exchange at the Foundling Museum) I’ve undertaken to ‘Teach someone to cook’. It says this underneath the cup. I can cook, fortunately, so one vital qualification is in place at least. (Or maybe I just think I can, and my partner does it all really?) Like Algernon Worthing’s piano-playing, my cooking may not be accurate – anybody can cook accurately – but I cook with wonderful expression.

In my initial enthusiasm, I imagined that there’d be plenty of people who’d find this ‘good deed’ genuinely helpful, but in fact the how-to’s of cooking are so ubiquitously available – to those who want to know – that it’s only quite small children who aren’t accomplished chefs already. And they all have long waiting-lists of adults who want to make cup-cakes, when the children are prepared to humour them. So, rather than just give some obliging victim literal instructions on how to boil the proverbial egg, I’ve decided to interpret the good deed less literally.

Since I’m quite apt to burn things because I’m thinking about writing my book, and I like reading cookery books but not cooking from them, my cooking is rather idiosyncratic. (It’s most often done in tandem with my partner anyway; a dance in a small kitchen.) I’ve tried to analyse something about its particularity that’s communicable, that might pass for ‘teach’. The result is The Cook’s Tale – these impractical suggestions about to how to be a cook, both in the imagination and in the kitchen.

It’s an enormous subject. ‘Everyone knows it takes ten years to make a cook,’ according to Edouard de Pomiane, who nevertheless wrote Cooking in Six Lessons and then, emboldened, Cooking in Ten Minutes, or the Adaptation to the Rhythm of our Time, a 1948 book:

‘for the midinette [young Parisian milliner], for the clerk, for the artist, for lazy people, poets, men [sic] of action, dreamers… for everyone who has only half an hour for lunch or dinner and yet wants half an hour of peace…’

But, on an even smaller scale, in hommage to Edouard de P., here are Six Ways to be a Cook:

1) Be a Storyteller

All cooking tells stories; of journeys, of homecomings, of seasons and weather, feastdays or festivals, of places and relationships. There are the stories of who we are and where we come from or want to go; history and homeland, tradition and travel. Or, there are stories of how we might imagine ourselves or our lives; fantasy and re-invention, experimentation with other possible ways of being and thinking. There are entire autobiographies; the ‘signature dish’ which is a statement of self – often fictional.

The question is, what sort of story do you want to tell?

A simple narrative of harvesting or gathering, making fire and drawing water; basic human survival stories? Or a festival tale, giving thanks or remembering some old fable of deliverance, some gunpowder plot? Or is it to be a celebration of place and people, with the local specialities of home, telling what grew or got traded there, how it could be cooked? Or does it mark the passage of time, the turn of the year bringing the first asparagus or the last russets? Or will it be a more individual story, your own mythology in a pan?

Some famous recipes arrive with their myths ready attached; references to the provenance of the recipe or its special message. The imam fainted with aubergine-induced delight, Napoleon’s chef improvised the odd combination of sauce Marengo on the battlefield, King Alfred burnt the hearth-cakes while he was reading…

So, to cook as a storyteller is to celebrate the art of life, of pleasure, of discovery; make statements of place or expressions of self. Your stories can be simply told, subtly revealed, or merely suggested – raw, charcoal-grilled or steamed – in the preferred style of the moment, and they will add imagination to the flavour.

2) Be a Traveller

Travel (armchair is fine), sail off on culinary voyages of discovery, return with new spices, new ideas of possible tastes, enlarged horizons. Go Round the World in Eighty Dishes, as Lesley Blanch’s charming cookery book says, without leaving the kitchen. Many of the best cookery books are travelogues, like Claudia Roden’s Book of Middle Eastern Food, full of stories about food (lowering baskets out of the windows to be filled with falafel in the street); the experiences of eating and cooking, colours and textures and city sounds, which evoke a whole culture.

One of the most evocative trips away, and certainly the bossiest, is Greek Monastery Cookery by Archimandrite Dositheos, who quotes St Gregory the Theologian on ‘the magic and wizardry of the cooks’ and reassures the under-appreciated that ‘cook saints are known to God’. By contrast calmer, Elizabeth Romer’s The Tuscan Year follows the seasonal cycle of life and food-harvesting on Silvana and Orlando’s Italian farm, a place where the style of cooking is fundamental to the spirit of place.

As a travelling cook, or cooking traveller, you can conjure up an experience of otherness through eating; a brief visit to a strange land in its essence. By recreating this once-foreign food, whether from an evocative book or from memories of travel, you take another voyage in the imagination.

On your way, any simple picnic (or cold collation of genius) can be a poem of travel; pilgrimage, lovers’ meeting, harvest rest, journey break.

3) Be a Rememberer

Proust’s moment of intense recall, prompted by the taste of the madeleine dipped in tea, is referenced so often because it expresses such a common human experience so profoundly. Proust invokes the shared language of food, whether it’s a dunked cake or a certain kind of strawberry, describing its extraordinary power to summon up the past. Tastes and scents can instantly restore a time apparently forgotten (or lovingly remembered); this is one of the cook’s alchemical powers.

Often, the memory is of childhood, but goes beyond mere nostalgia for childhood foods or the security of the familiar, comforting though that might be. It’s closer to the mystery of goût de terroir, the indefinable taste of the land, which can’t be mistaken for anywhere else. There’s a strong element of ancestral reminiscence, as well as wishful-thinking folk-memory, in our individual recollections.

My grandmother cooked an old-fashioned egg custard: as a child early in the 20thC she’d been taught to make it by someone older (who was inevitably a Victorian, probably born mid-19thC). It was a Dickensian, if not a Jane Austen, taste – delicious but not usual, now lost. I don’t know how she did it, though it included nutmeg, and all the ingredients had to be ‘very pure’.

Time travel to that other country of the past is a cliché, jam-making grandmothers or baking aunts shamelessly exploited on the labels of mass-produced stuff. But it works, sometimes. You can’t always conjure up epiphanic moments of revelation, but remember their possible immanence.

4) Be an Inventor

Interesting cooking – expressive rather than accurate – tends to be the result of interpretative straying from strict recipes, of improvisation with unlikely ingredients, or even of downright eccentricity. It’s an expression of personality, or personal style; a translation into your own language. Originality, flair, individuality, are the hallmarks of the inventor cook.

In Recipes from Scotland (by F. Marian McNeill, also author of The Scots Kitchen), there’s a fine recipe for Kingdom of Fife Pie. It bears little resemblance (in my memory) to the magnificent, mythic edifice my mother sometimes made, with whole eggs – can they really have been in their shells? – twiggy sprigs of herbs, succulent chunks of roast game, saucer-sized mushrooms, haggis sausages, heels of smoked cheese, fennel roots or whatever took her fancy, all concealed within the enveloping pie-crust. This utter transformation into a flamboyant renaissance dish, which contained kingdoms indeed, was very characteristic.

To be an inventor in the kitchen, you don’t need to be quite so wild. Chacun and all that. But you can avoid by-rote, measured-out, recipe-following joyless uninventive food-preparation – forgetful of story, memory, travel or anything else – which leads eventually to the dire routine of left-overs which Davey describes in Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love: ‘Monday, poison pie, Tuesday, poisonburger steak, Wednesday, Cornish poison…’ and so on.

5) Be a Friend

‘When one goes into a shop to buy a cake, one gets nothing but a cake, which may be very good but is only a cake; whereas if one goes into the kitchen and makes a cake because some people one respects and probably likes are coming to eat at one’s table, one is striking a low note on a scale that is struck higher up by Beethoven and Mozart.’ (Rebecca West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon)

This is the perfect statement of the cook’s artistry, a high claim. It also celebrates the loving cook, the friend who understands food-making as a language of hospitality, with all the symbolism of breaking bread and sharing salt, the friendly obligations of host and guest. Even if you’re hastily buying a meal ready-made from the deli, however much Rebecca West might think ‘it may be very good but it’s only a meal’, you can improvise it hospitably or impatiently, with evident results.

If you do make the cake or whatever it is, and make your friends welcome, you also create the possibility of a happy occasion which is a work of art in itself, when all the pleasures of wine and food and talk add up to something more than the sum of the parts, perhaps like the friends’ supper together in Virginia Woolf’s The Waves: ‘Now is our festival, now we are together.’

(On the subject of loving cooks, ‘Be a romantic’ probably doesn’t need to be said. ‘A dinner of herbs where love is’ – whether it’s a sandwich banquet, cold collation, fry-up at midnight or surprise fridge-feast – this is the cook as romantic. A carefully-prepared dinner might be seductive, or an emergency meal erotic; the loving cook will create what the occasion demands without difficulty, only perhaps recalling Edouard de Pomiane’s invaluable advice about garlic soup: ‘if there are two of you, consume this fragrant soup in unison or the one who refrained would find it hard to bear the other’s proximity during the evening.’)

As a loving cook you can also be a healer, a provider of comfort and sustenance, with a whole life-enhancing art of tempting the appetite and maintaining the pleasure in food for someone who’s not well. All you need is empathy, inventiveness, and maybe most of all the happy idea that food cooked with love can be almost magically restorative.

Food as love can be burdensome for the force-fed guest, there can be confusion about elaborate or expensive cooking being more giving. As a friend, you need to be able to make food that’s possible to accept and genuinely offered, which leads inexorably to…

6) Don’t be a Monster

‘Unquiet meals make ill digestions’ (Shakespeare, Comedy of Errors)

The monster cook uses food as a weapon or instrument of torture; a source of unholy power for social blackmail or manipulation, a travesty of hospitality. The monster cook is a show-off who perceives food as a status symbol, and offers it over-elaborate, fiddled-with, too rich and designed to impress rather than please. (This sort of cook just won’t accept it if you’d prefer your food field-harvested, not abattoir-slaughtered.) The monster cook might not be above spitting in the sauce.

The monster cook indulges in mind-games; obliges people to eat what they don’t want or stops them having what they’d like, trades on their guests’ anxieties about eating, and finds it entertaining to cook or eat living creatures, or those that have been cruelly treated by being stuffed, starved, boiled alive or whatever. (Let’s not forget all those legends of unobservant people eating their relations served up to them in pies.)

The monster cook, in fact, isn’t a cook at all, but a sinister example of how not to be one.

Coda

If there’s no set rule for how to be a cook, there are these various possibilities to keep in mind. If you cook as a storyteller, traveller, rememberer, inventor, healer, friend or lover (but preferably not monster), you know how to be a cook.

My final excuse – I mean reason – for not giving more literal instructions; it’s futile, as this last exchange between the Mad King of Chichiboo and his temperamental cook, Cullenda, demonstrates:

‘But how can you tell when it is hot enough, unless you have had proper lessons?’ she asked.

‘When you can smell the cheese burning of course SILLY,’ said the King.