This year of grace 2015 is almost confusingly crowded with war anniversaries: Waterloo, Gallipoli, Dunkirk, VE Day, and more. One famous victory with its commemorative station, a notorious and costly disaster, a ‘glorious retreat’ which became a matter of national pride, peace at last. One hundred years between the great battles of 1815 and 1915 compares with the relatively brief timespan separating ’15 from ’40 – a mere twenty-five years.

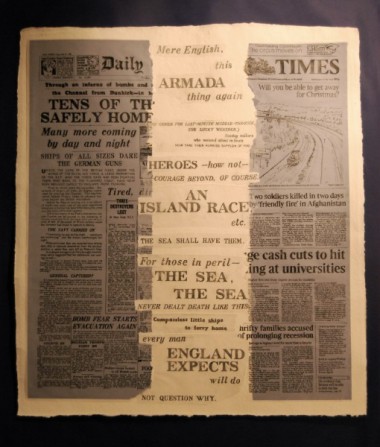

The problem with these anniversaries is that they can be the opportunity for essential human rememberings, dredgings of collective memory which come up with treasure, deep contemplations of history – or crass appeals to nationalism, in the worst sense, and the glorification of war.

In 2014, at the centenary of the outbreak of WW1, No Glory – the group of artists, actors and writers including Carol Ann Duffy – expressed their concern that memorial events would be exploited to promote militarism and celebrate the powers of destruction, rather than to honour the dead and acknowledge the personal sacrifices of all involved in such conflicts (which, in terms of WW2, we’re still living with, in a long aftermath). They hoped to encourage cultural events which would ‘mark the courage’ of those involved but also remember ‘the almost unimaginable devastation’ and ‘ensure that this anniversary is used to promote peace and international co-operation.’

It’s important for us to find ways in which to make an act of remembrance which fully acknowledges courage and honour, suffering and endurance, the many different modes of resistance to the forces of darkness – and yet doesn’t degenerate into a festival of militarism, or an unquestioning acceptance of war as a ‘necessary evil’.

The way in which the First World War is perceived has been drastically influenced by its portrayal in art – in the work of war poets, especially those like Wilfrid Owen who wanted to ‘make it stop’, the wartime art of Paul Nash or Stanley Spencer, haunting memoirs like Vera Brittain’s filmed and re-filmed Testament of Youth, Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End or Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (both also filmed), the elegaic music of Vaughan Williams and his contemporaries (and later, Britten’s War Requiem), and of course Joan Littlewood’s subversive classic Oh What a Lovely War – to name merely a few of the best known. All these are powerful memorials, in diverse ways, but it would be difficult to interpret any of them as pro-war.

Such works of art make it possible for us to commemorate, protest, explore, lament, re-examine, imagine, narrate, compare, question, and above all perceive such events in all their diverse complexity, light and shade, humour and drama, tragedy and unexpectedness. The development of narrative history projects also creates a complementary mosaic of remembered fragments which change and enrich our understanding of the past, and many artists work with these sources to make new kinds of art.

The anniversaries of WWII are even more complex; the armies march nearer to us in time, there are still many survivors, eye-witnesses, close relations involved. The motives for war were so different that even pacifists of the previous war accepted the need to arm. But that makes the need still greater for memorials which ‘ensure that this anniversary is used to promote peace and international co-operation.’

I believe that one such is The Dunkirk Project, set up by Liz Mathews five years ago on the 70th anniversary of Dunkirk, which developed from research for her monumental artist’s book, Thames to Dunkirk. The project combines art and poetry about that extraordinary moment with individual stories of the event from many different contributors. For 2015 the project is being relaunched, with live coverage of the evacuation as it takes place day-by-day, from 26th May to 6th June, and new additional material.

There’s now a page of Dunkirk Phossils by Charlie Bonallack (grandson of BG Bonallack whose poem Retreat from Dunkirk was lettered by Liz Mathews on Thames to Dunkirk, with Virginia Woolf’s words), updated and revised contributions, new stories, more poems, more images – to make an even more vivid panorama of the Dunkirk story.

As the poet Jeremy Hooker wrote in response to it: ‘This is a wonderful project. True remembering is essential to our humanity.’

Leave a comment